Taking their inspiration from the sinuous poses of Indian sculpture, Ramachandran and

Hirstein propose that one route to the perceptual essence is the principle of caricature.

By exaggerating the characteristics of the subject, the artist draws attention to its

essential features, in an analogy to the "peak shift " or enhancement of trigger features in

animal behavior that has evolved to maximize the behavioural response to critical stimuli.

These authors go beyond the conventional analysis of caricature in cartoons alone to

argue that a similar process of perceptual caricature is one of the key principles of art as

a whole. By enhancing the essential in the chosen subject matter, the artist can create

an image (graphic or sculptural) that resonates in our memory and stands as a cultural

symbol.

The trick is to define which features are essential and which are incidental. Another way

to say this is to ask which direction in N-dimensional feature space should the features

be moved in order to make the desired enhancement? The usual assumption for facial

caricatures is to assume that the feature shift for the caricature of a particular face

should be to enhance its difference from the form of the average face.

Generalizing to the

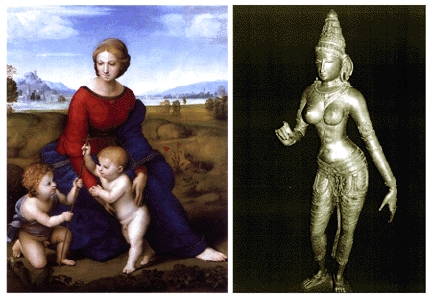

core artistic subject of the human figure, Ramachandran and Hirstein propose that the

relevant anchor point should be the form of the average body. The artistic representation

of female form, therefore, should be enhanced in a way to exaggerate the features that

distinguish the two sexes, accounting for the enhancement of sexual expression in

Indian statuary. For each kind of enhancement, this explanation requires that one identify

both the form of the anchor point and the appropriate direction away from it, which may

not be so easy for landscapes or scenes of particular human activities. Indeed, can one

talk of a definitive essence at all when art may be viewed not as an object but as a

developing relationship between the artist and the art work, and subsequently with the

viewer?

An ultimate problem with this analysis, as the authors make clear, is that art is a vastly

diverse enterprise that may not be so readily amenable to a simple treatment. Given a

principle like the peak shift away from average, one is naturally anxious to try it out on a

variety of classic examples. For example, enhancement of sexual features does not

seem to have been a hallmark of Renaissance art in the West. That had to wait for the

Baroque and Rococo eras, when the riot of depictions of Gods and Goddesses conform

well to the predicted peak shift away from each other, with bold muscular Gods bending

lithe delicate Goddesses to their will. It seems that Renaissance art is rather

characterized a deeper principle whereby the artist tries to capture the average, or

typical, image of the subject matter itself rather than shifting away from it, as in

Raphael's 'Madonna of the Meadows'. This is perhaps exemplified by the earlier history

of art, from the Greek sculptures of the era of the Venus di Milo or the discobulos, whose

appeal seems to be the elegant modesty of their sexual features, to the Renaissance

ideal of the Mona Lisa, which is almost androgynous. Capturing the typical pose of the

subject matter in this way is such a basic principle of art that Ramachandran and

Hirstein seem to have missed it, but no comprehensive analysis of the issue can afford

to exclude it. Much Renaissance art consists of depicting the same pose repeatedly until

a canonical form is achieved, as in the 'madonna and child' or 'Christ on the cross'.

Figure Typical versus exaggerated expression of sexuality

Following the shift principle, these authors outline seven other interesting principles,

drawn from Gestalt psychology and neurological sources that they believe constitute the

deep structure of the art experience. The case for each principle is generally made with

ingenuity and flair. In brief, these are the isolation of key aspects of the composition,

grouping of related features, contrasting of segregated features, perceptual problem

solving to extract the relevant information, a preference for generic views, the use of

visual metaphors and, finally, symmetry. These two neurologists reveal much more of

the brain processes that are likely involved in implementing these principles than would

most art critics. But it is unlikely that many art critics would regard these principles as

exhausting the repertoire of art principles (even accepting the caveat that there is much

that is individual in art and not amenable to a principled analysis). Nothing is said about

the widely recognized principle of balance in composition, of the power of the centre

emphasized by Rudolph Arnheim, or of the dynamic interplay of visual forces

emphasized by Wassily Kandinsky, for example.

Of the eight principles delineated, the one that may be of most interest to artists is that of

perceptual problem solving. Curiously, the section addressing this principle seems to

have been lost in the main text, but it is clearly identified in the summary. Had they

included the section, perhaps it would have included an extensive analysis of how the

principle accounts for many of the diverse manifestations of 20th century art. One of the

characteristics of 20th century art is that it included (among other things) a succession

of styles of abstraction: fauvism, cubism, dadaism, futurism, abstract impressionism, op

art, minimalism, and so on. Even in earlier representational trends, extremes of

representational style such as impressionism, pointillism, expressionism, photo-realism

and so on are themselves forms of abstraction. The point is that any form of abstraction

requires the viewer to make a perceptual effort to extract the theme of the painting

(compared with the essentially effortless perception of representational art). This effort

itself forms an essential component of the artistic experience; by slowing down the

perceptual processes of decoding the art work the viewer becomes aware of their

evolution and interplay over time, and then experiences a sense of achievement when

the full composition falls into place (or of continued mystery if it does not). Thus, the

problem solving principle, evoked to account for the appeal of hiding the female form

under diaphanous garb, could account for much of the development of 20th century

abstract movements (which are hard to shoe-horn into the other seven principles!).