The cultural dominance of art based on realism was a late development

largely confined to Western culture. With it went a powerful link between

Christianity and the academies, which insisted on a selective approach to

nature in order to record God-given appearances and communicate

Christian virtues and meanings. Moreover, painters should not merely

copy every detail but select only what was most beautiful and significant

according to universal academic standards. Inevitably these standards

slipped towards the depiction of ideal forms of the classical world that

paradoxically were considered timeless. Nevertheless, painting’s first aim

was to represent facts about the visible world and the way this is seen by

the eye. Retinal realism came to the forefront with explorations of the

rules of perspective. Every important facet of the subject was to be traced

through space, into the lens of an eye, and from there plotted in two

dimensions as an image with the illusion of depth. Later, painting as a

method of representing the seen world began to be combined with the

personal expression of the painter’s feelings and his creative power to

present action and emotion. The aim was still to capture a visual

phenomenon. However, expressionism began to dominate the creative

process and the painter’s private feelings eventually came to carry the

main burden of the pictorial message. Finally, it was the mind that lay

behind the eye that came to dominate the process of turning perception

into representation.

Painting inhabits a mental world where the cerebral cortex projects its

virtual images of imagination and feeling. It would be useful to pin down the

point at which the trickle of efforts towards cortical abstraction became a

torrent, and 1907 is a good a year as any. This was the year Picasso tried

his first experiment in deconstructing the human figure to intensify

expression. Les Demoiselles d’Avignon for the first time formulates the

Cubist idea of reproducing volumes fundamentally as rhythms of surfaces

(Fig 6). The images remained attached to the objects but became freed

from their original meaning. It was also about the year 1907 that Kandinsky

began to assemble examples for his theoretical essay ‘About the

Spiritual in Art’ which was to promote a new form of perception and

representation in which painting was to be freed from reality and have its

beginnings in virtual pictures of the mind.

Fig 6 Picasso: Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907)

A dramatic return to fundamentals through the nude was inaugurated with

two pictures painted in the year 1907. By virtue of the great impact of these

paintings, 1907 can conveniently be taken as the starting-point of 20th-

century art. The works are Matisse's Le Nit bleu and Picasso's

Demoiselles d'Avignon; and both these cardinal, anti-academic pictures

represent the female nude. This revolt of 20th-century painters was not

against academism: that had been achieved by the Impressionists. It was a

reaction against the doctrine, with which the Impressionists implicitly

agreed, that the painter should be no more than a sensitive and well-

informed camera. And the very elements of symbolism and abstraction -

which made the nude an unsuitable subject for the Impressionists,

commended it to their successors. When art was once more concerned

with concepts rather than sensations, the nude, which by that time had a

long history of academic development and a profound influence on what

was acceptable as art, was the first concept which came to mind.

Matisse: La nit Bleu (1907)

Matisse and Picasso are almost antithetical characters, and their reactions

to the nude have been very different from one another. Matisse was a

traditionalist picture-maker whose life drawings could almost be mistaken

for those of Degas, and like Degas or Ingres he deduced from the naked

female nude certain pictorial constructions which satisfied his sense of

form and which were to obsess him for a great part of his life. The Blue

Nude represents such a construction. It was an important part of himself,

and he not only carried out the same pose in sculpture, but also brought it

into numerous other compositions. This is the first investigation of the use

of the nude as an end in itself or as a means of creating significant form.

The revolutionary character of Matisse's picture resides not in the end but

the means. That enjoyment of continuous surfaces, easy transitions and

delicate modelling, which had seemed such an essential factor in painting

the nude, is sacrificed to violent transitions and emphatic simplifications.

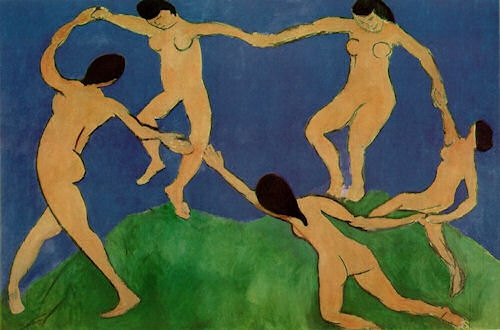

This problem of simplifying a female body was to obsess Matisse and all

the most intelligent painters of his time. The classical system had been the

hard-won solution of the problem, and when it was no longer acceptable

some other form of simplification had to be found. Matisse sought for it in

an earlier phase of the Greek tradition, and produced La Danse and La

Musique, the two decorations painted for the art collector

Shchukin. He

sought for it in Japanese prints and in the Islamic Exhibition of 1910.

Sometimes his search is successful but sometimes he seems to grow

exhausted in pursuit of a quarry. Such is the impression we receive from a

series of eighteen photographs taken of the stages in the completion of a

painting known as the Pink Nude. Almost thirty years have passed since

he began work on the Blue Nude, but the first stage of his new quest is

remarkably similar in pose. He is still clasping the same obsession. But the

handling is less vigorous, as if the simplifications had to be achieved by

argument and not by instinct.